I think the original blackish finish of B&S parts was niter bluing; a 50/50 mixture of sodium nitrate and potassium nitrate was heated (and melted to a clear liquid) to 600 deg. F. for only perhaps 5 minutes; color desired can range from blue to black depending on time in the bath; this the U.S. Armory method of bluing. Just heating to blue does not provide nearly the same protection from rusting.

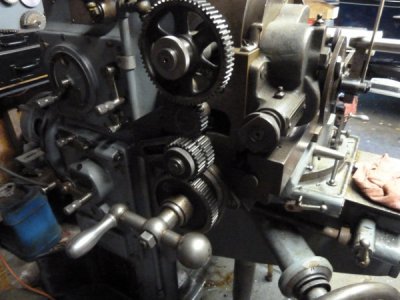

My B&S dividing head does not seem to have a spring behind the plunger, but I have not looked to see if it had one or if it is there and broken; keeping the plunger engaged on the rapid indexing plate under cutting conditions does not seem to be a problem, as the slight taper of the plunger and hole in the plate hold quite tightly when engaged; also I do not note any evidence of the detent bullet in the "feel" of the plunger when engaging or dis engaging the plunger, perhaps I need to take it apart and have a look?

Somewhere on Hobby Machinist, I posted the entire American Machinist technical article on U.S. Armory method of bluing ( with express permission of American Machinist) It bears reading if you can find it. I had a B&S #2 universal mill of about 1906 vintage; I used it in my machine shop for about 30 years, then restored it to take with me in retirement; well, along came a 1942 model with more features and the universal milling attachment ( all angles), so I sold my restored machine, but as part of the restoration, I blackened all the bare steel parts for rust protection as they were originally and it really does a good job at preventing rust. It works on cast iron too, but it takes much longer and does not give the intense black finish as it does with steel. Chemical "gun blue" is nearly worthless for rust protection and the selenium based "cold black" solutions are also quite poor. The only drawback to the Armory method and the "torch blue" methods is that both draw the temper of hardened articles to the "spring temper" level, that is, I think, in the high 30s Rockwell C range of hardness.