Single point threading on an ordinary lathe is not a big deal. Stack the deck in your favor while eliminating the chances for early failure and being scared to death. Practice the moves a bit, then get the mostly finished part you are making that already has 20 hours work into it and the final operation is an ordinary external thread -- but you have never tried making a thread before...

First try a couple test passes. Set up your part you are going to practice on, get all the gearing and other settings correct on the lathe, move the tool right up next to the end of the work, screw in the feed to make the cut, and then... STOP!!!

It is dumb to try to accomplish all the things you need to get perfect results down solid on your first try. So, let's make this a lot more simple and learn one thing at a time, and learn it well.

First, back the tool away from the end of a longer test piece, giving it plenty of room, say tool 3" from the end of the work. Set the tool depth so it will not touch the work at all. Then the cutting tool should be able to run over the test piece for a LOT of revolutions before it hits the chuck or anything else in the path.

OK, half nuts disengaged, everything set up so you can very easily shut the thing off before hitting anything. Start the spindle turning at the lathe's slowest speed. Work well away from the work for a while, and practice shutting it off quickly and efficiently. Repeat until it is in muscle memory and you no longer need to look at the knobs and handles to find them.

Then practice engaging and disengaging the half nuts well away from the work. Do it slowly and feel what is going on. The lead screw is usually Acme, which means the half nuts ride on the flats if you start the engagement too early, and then fall into place properly. So try it over and over maybe 50 times, trying a little bit before it drops in and then go later and later until you miss the proper tooth on the threading tool. Soon you will have the feel for it, and will know that moving the lever a little bit early is not a problem, it only postpones dropping into the correct tooth. Right on the number works perfectly, and engaging too late, even by a little, can make you miss entirely and cut a double thread. With a little practice and knowing nothing can go wrong by dry practicing, you will soon be doing it confidently every time. Now try starting close to the end of the work, with the tool pulled out just safely far enough that it will not engage the work as it traverses. Start three inches away and engage the half nuts, and then try to stop the cut right at the start of the work. (A miss means that you may have run the tool into a face if it was a for real job...) Keep trying it closer and closer to the end of the work, stopping it before the work, until you fail. Now you know what you cannot do. You probably also notice that you really don't waste much time engaging the half nuts a safe distance from the work, safe enough to easily disengage them prior to reaching the work. Practice it over and over, getting the feel and the muscle memory, and learning and getting better with every try. Now add to the equation backing out the cross slide a quick full turn at the same time the half nuts are disengaged -- without looking at them, only looking at the work. More practice, until it all becomes natural. It doesn't really take that much time to feel confident when you advance your skills slowly enough that failure is unlikely.

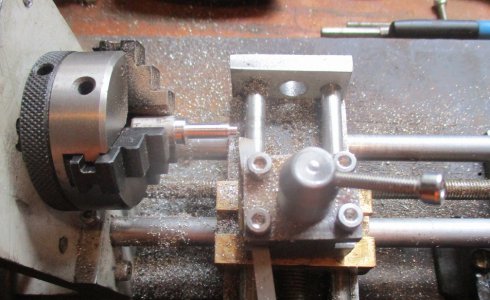

When you have the muscle memory down, you are doing it each time the same way, and you don't really even need to think about the quick disengagement sequence, then you are ready to cut metal. Choose something soft like an aluminum bar, perhaps 1/2" to 1" in diameter, long enough to extend several inches out from the spindle. Set up the lathe feed rate for a relatively slow feed, perhaps something like 24 tpi or 1mm. Bring the tool over the beginning of the metal with the carriage hand wheel, and then move the cutting tool in until it just touches the metal. Zero the threading dial, back out a quarter turn of the dial, and move the carriage to the right until you know that you will be ready for an instant stop of travel and tool back out before hitting the work. (I won't get in to threading dial number rules here, just use the same number for each cut until you want or need to learn more. It is a bit slower, but it works for all threads, as long as it is English threads on a Imperial lead screw machine, or metric threads on a metric lead screw. Crossing that boundary will require another lesson.) Turn the cross slide handle back to where you touched of at, and then add .005" (or .1 mm). Run the cut again, this time you will get a light cut with a curl of metal coming off. Disengage the half nuts at a previously marked point as best as you can, turning the feed knob out one revolution at the same time. Go back to the beginning, turn in the cross slide another .005" (.1mm), and repeat as before, continuing until the threads come almost to points. See how nice it looks (if you did it right!). Making a proper thread to mate another threaded part is beyond this already far too long post. There is no reason to be afraid of threading if you work up to it one simple step at a time, trying things that are as simple and safe as possible. Save the fussy stuff until you feel up to it.

Please do not use short cuts. Learn each thing in the logical sequence. We must learn to crawl before we learn to walk, and to walk before we run. Patience, grasshopper...