- Joined

- Feb 5, 2015

- Messages

- 662

(previously posted on a woodworking forum and edited for posting here)

Ten years or so ago, I bought a couple of imported trim routers. One was used in a hastily-built fixture for installation on my vertical mill as described in this topic:

http://hobby-machinist.com/index.php?topic=410.0

The other router was intended as a spare (they were cheap, imported tools - not anticipated to last long). I've since installed the spare in a little shop-built 12 x 12 router table. This compact assembly stores under a workbench or on a shelf and is one of the handiest things I've made. It's a pain to move a 3-1/2 horsepower Milwaukee around for tool changes if its hanging under a router table - especially for something trivial like corner rounding or chamfering.

This small clamp-on router table is useful for many light-duty jobs and allows quick tool changes. It's sized to accommodate any convenient edge: workbench, dining room table, sawhorse, tailgate of pickup and so forth. The assembly is small and light enough so that it can be mounted at 90 degrees for horizontal routing, on a sawhorse for example (possibilities: inletting a door lock, mortising long timbers and the like).

A couple of clamps and a scrap of hardwood can be used as a temporary fence as shown below. The router table is attached to a pull-out cutting board in the kitchen, set up for producing rabbets on the ends of shelf boards. There is NEVER enough storage space in a kitchen, I'm told. This little shelf project was made for a disabled friend and other than the table, a Skil saw and a straight edge, no other tools needed to be transported.

The applications are limited to imagination (and horsepower, naturally). Using a slotting cutter, the little table + trim router makes a handy plate joiner. An inexpensive speed control is useful for large-diameter cutters and when routing aluminum.

With a corner-rounding (or chamfering) carbide cutter installed, the router table can quickly de-burr non-ferrous sheet parts that have been sheared or sawed. Swiping a candle stub (or stick lube for slotting saws) across the edge of the sheet stock before feeding through the router is a good idea - better finish and longer tool life.

Chuck a small carbide burr in the router and the edges of some ferrous materials can be processed - lubricating the edge of the material, as above, is also recommended. In either case, clamping the router to a sawhorse parked in the driveway allows sharp slivers to be easily swept up and deposited in the scrap can. (If the router is used in the shop, the chips get spewed around, picked up in my shoes and deposited on the living room carpet, disturbing domestic tranquility).

NOTE: ANY router with air inlet or cooling vents on the spindle end of the housing is unsuitable for inverted mounting in a router table if metal is being routed. Metallic debris entering the router body will not only ruin the bearings but will cause potentially dangerous electrical damage. If one is considering the use of a router for de-burring metal, this problem needs to be addressed. One simple means of doing this would be a light, sheet-metal "L" or "U" bracket secured to the router body with a clearance hole for the shank of the router cutter.

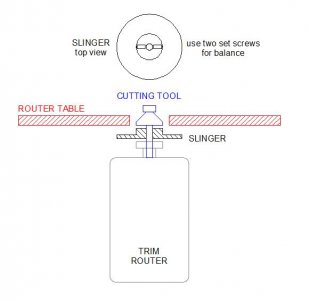

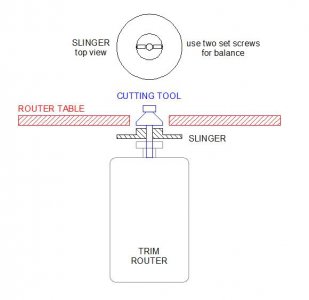

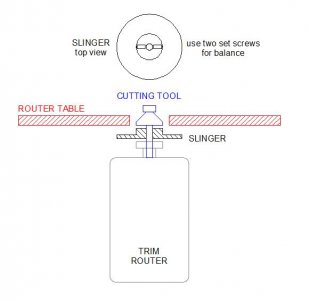

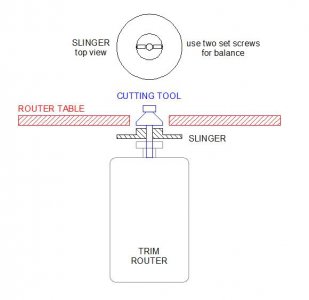

Temporary expediencies, such as taping around the hole in the router table, may be tempting but are unsafe. A sheet metal cover would be inconvenient for removing the router from the table to change cutters so I thought a better idea would be a device similar to an "oil slinger", common in many small engines and located next to shaft seals. I was a little hesitant at first because of the high spindle RPM but I crunched the numbers and the ring stress for typical slinger dimensions is less than 500 PSI at 15,000 RPM - nothing to be concerned about.

The following sketch shows two set screws holding the slinger to the shank of the router cutter. If used, these should probably be the "ny-lok" self-locking type of set screw - one of these screws working loose would smart if it struck a sensitive body part. After thinking about it for a minute, if the slinger is made in one set-up, bored and then reamed for the cutter shank, there's probably no need for securing it to the shank. When the spindle spools up, the slinger will most likely migrate upward (vibration) until it seats against the bottom of the cutter - there is negligible force involved so no danger of pulling the cutter out of the collet.

Frankly, although I SHOULD make a nice slinger, I've been using something <ahem> a little lower-tech:

This is a tin-can lid with a 17/32 hole punched in the middle. It fits the spindle snugly, covers the vent holes completely but allows the free flow of air and is light enough not to cause a balance problem. Disadvantage is the sharp edges, even after de-burring; when tightening/loosening the collet nuts I have to be cautious. When the router is operating, the sharp edges are under the table, out of the region where a finger might be inadvertently inserted (note the Darwin Award possibility). If the sole purpose of the router table was routing wood, then the air exiting the cooling vents blows the chips away and no protective cover is required.

Making the table was straightforward once a desirable configuration was determined. The materials were dug out of the scrap box: waferboard and fiberboard for the top, scrap pieces of western ash for the remainder. The two clamping handles that attach the table to a work surface and the single handle that clamps the router to the table are standard tool parts, purchased at the local hardware store as were the remaining fasteners and the threaded rod.

After installing a pair of long studs (threaded rod) through the table top and the clamps (secured with nuts/washers at both ends), the table was glued up. A thin piece of fiberboard was contact-cemented to the top, providing a smooth working surface and hiding the counterbored holes and nuts attaching the threaded rod. After allowing a day for glue cure, I clamped the assembly to the vertical mill table and used a boring head to produce the two holes that align the trim router perpendicular to the router table.

Because the body of the router near the spindle has a tapered draft angle, the bores obviously needed to be of differing diameters. (The diameters were rough cut with a hole saw before the individual pieces were glued together.) The upper router guide (the lower one in this photo) is saw-split and equipped with a hand-screw and a pronged-nut for clamping the router at the desired height.

One feature that didn't occur to me originally (which I intend to add) is a set of replaceable table inserts to accommodate various diameter cutters. This is a safety provision that is especially desirable when routing aluminum - any extra clearance between cutter and table creates the very unsafe possibility of kick-back.

A safety precaution (which I also observe when operating my jointer) is to use a "cement float" to push the work across the cutter. The "float" has a textured rubber bottom that provides lots of friction against dry aluminum and a handle that is well out of the way of the cutting tool. It is posed in the foreground with a few other home-made implements also intended to keep my hands away from sharp tools:

I've always thought that using machine tools for making gifts is very helpful to justify the existence of the tools to wives. I made a near-identical router table for a brother-in-law last year as a Christmas gift. My brother-in-law has almost no room for his woodworking tools (his wife insists that garages are for automobiles - very odd) so he appreciates the fact that he can clamp the little table to a sawhorse for use, then unclamp and store it elsewhere.

Ten years or so ago, I bought a couple of imported trim routers. One was used in a hastily-built fixture for installation on my vertical mill as described in this topic:

http://hobby-machinist.com/index.php?topic=410.0

The other router was intended as a spare (they were cheap, imported tools - not anticipated to last long). I've since installed the spare in a little shop-built 12 x 12 router table. This compact assembly stores under a workbench or on a shelf and is one of the handiest things I've made. It's a pain to move a 3-1/2 horsepower Milwaukee around for tool changes if its hanging under a router table - especially for something trivial like corner rounding or chamfering.

This small clamp-on router table is useful for many light-duty jobs and allows quick tool changes. It's sized to accommodate any convenient edge: workbench, dining room table, sawhorse, tailgate of pickup and so forth. The assembly is small and light enough so that it can be mounted at 90 degrees for horizontal routing, on a sawhorse for example (possibilities: inletting a door lock, mortising long timbers and the like).

A couple of clamps and a scrap of hardwood can be used as a temporary fence as shown below. The router table is attached to a pull-out cutting board in the kitchen, set up for producing rabbets on the ends of shelf boards. There is NEVER enough storage space in a kitchen, I'm told. This little shelf project was made for a disabled friend and other than the table, a Skil saw and a straight edge, no other tools needed to be transported.

The applications are limited to imagination (and horsepower, naturally). Using a slotting cutter, the little table + trim router makes a handy plate joiner. An inexpensive speed control is useful for large-diameter cutters and when routing aluminum.

With a corner-rounding (or chamfering) carbide cutter installed, the router table can quickly de-burr non-ferrous sheet parts that have been sheared or sawed. Swiping a candle stub (or stick lube for slotting saws) across the edge of the sheet stock before feeding through the router is a good idea - better finish and longer tool life.

Chuck a small carbide burr in the router and the edges of some ferrous materials can be processed - lubricating the edge of the material, as above, is also recommended. In either case, clamping the router to a sawhorse parked in the driveway allows sharp slivers to be easily swept up and deposited in the scrap can. (If the router is used in the shop, the chips get spewed around, picked up in my shoes and deposited on the living room carpet, disturbing domestic tranquility).

NOTE: ANY router with air inlet or cooling vents on the spindle end of the housing is unsuitable for inverted mounting in a router table if metal is being routed. Metallic debris entering the router body will not only ruin the bearings but will cause potentially dangerous electrical damage. If one is considering the use of a router for de-burring metal, this problem needs to be addressed. One simple means of doing this would be a light, sheet-metal "L" or "U" bracket secured to the router body with a clearance hole for the shank of the router cutter.

Temporary expediencies, such as taping around the hole in the router table, may be tempting but are unsafe. A sheet metal cover would be inconvenient for removing the router from the table to change cutters so I thought a better idea would be a device similar to an "oil slinger", common in many small engines and located next to shaft seals. I was a little hesitant at first because of the high spindle RPM but I crunched the numbers and the ring stress for typical slinger dimensions is less than 500 PSI at 15,000 RPM - nothing to be concerned about.

The following sketch shows two set screws holding the slinger to the shank of the router cutter. If used, these should probably be the "ny-lok" self-locking type of set screw - one of these screws working loose would smart if it struck a sensitive body part. After thinking about it for a minute, if the slinger is made in one set-up, bored and then reamed for the cutter shank, there's probably no need for securing it to the shank. When the spindle spools up, the slinger will most likely migrate upward (vibration) until it seats against the bottom of the cutter - there is negligible force involved so no danger of pulling the cutter out of the collet.

Frankly, although I SHOULD make a nice slinger, I've been using something <ahem> a little lower-tech:

This is a tin-can lid with a 17/32 hole punched in the middle. It fits the spindle snugly, covers the vent holes completely but allows the free flow of air and is light enough not to cause a balance problem. Disadvantage is the sharp edges, even after de-burring; when tightening/loosening the collet nuts I have to be cautious. When the router is operating, the sharp edges are under the table, out of the region where a finger might be inadvertently inserted (note the Darwin Award possibility). If the sole purpose of the router table was routing wood, then the air exiting the cooling vents blows the chips away and no protective cover is required.

Making the table was straightforward once a desirable configuration was determined. The materials were dug out of the scrap box: waferboard and fiberboard for the top, scrap pieces of western ash for the remainder. The two clamping handles that attach the table to a work surface and the single handle that clamps the router to the table are standard tool parts, purchased at the local hardware store as were the remaining fasteners and the threaded rod.

After installing a pair of long studs (threaded rod) through the table top and the clamps (secured with nuts/washers at both ends), the table was glued up. A thin piece of fiberboard was contact-cemented to the top, providing a smooth working surface and hiding the counterbored holes and nuts attaching the threaded rod. After allowing a day for glue cure, I clamped the assembly to the vertical mill table and used a boring head to produce the two holes that align the trim router perpendicular to the router table.

Because the body of the router near the spindle has a tapered draft angle, the bores obviously needed to be of differing diameters. (The diameters were rough cut with a hole saw before the individual pieces were glued together.) The upper router guide (the lower one in this photo) is saw-split and equipped with a hand-screw and a pronged-nut for clamping the router at the desired height.

One feature that didn't occur to me originally (which I intend to add) is a set of replaceable table inserts to accommodate various diameter cutters. This is a safety provision that is especially desirable when routing aluminum - any extra clearance between cutter and table creates the very unsafe possibility of kick-back.

A safety precaution (which I also observe when operating my jointer) is to use a "cement float" to push the work across the cutter. The "float" has a textured rubber bottom that provides lots of friction against dry aluminum and a handle that is well out of the way of the cutting tool. It is posed in the foreground with a few other home-made implements also intended to keep my hands away from sharp tools:

I've always thought that using machine tools for making gifts is very helpful to justify the existence of the tools to wives. I made a near-identical router table for a brother-in-law last year as a Christmas gift. My brother-in-law has almost no room for his woodworking tools (his wife insists that garages are for automobiles - very odd) so he appreciates the fact that he can clamp the little table to a sawhorse for use, then unclamp and store it elsewhere.