- Joined

- Sep 7, 2015

- Messages

- 16

Hey everyone,

I am in the beginning of a new project: a 1/144th scale RC model of the Titanic. The catch is that I've built a wooden former over which I'll solder 1/2"x 2-1/2" 0.010" tinplated steel pieces to recreate the look of the riveted 1" thick steel plates on the original. Once, completed, I'll remove the wooden former leaving an empty shell.

I have soldered a test sample of brass pieces to see if it was possible and was happy with the results. I think the tinplate will also be fairly straight forward as far as soldering but I'm having a little trouble planning some aspects.

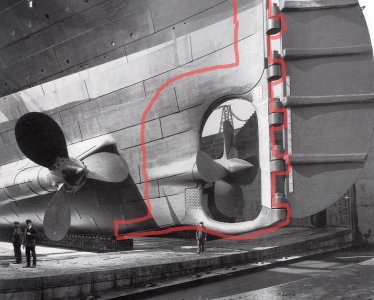

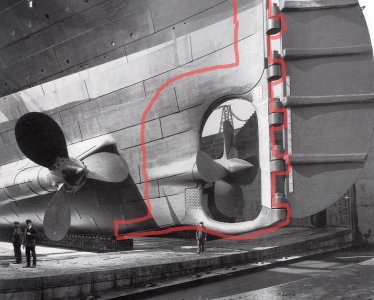

The stern section will have a frame constructed of brass that the aftmost hull plates will terminate at and anchor to. Here's a picture of what I will be attempting. The red outline is what the frame will look like underneath the hull plates, inside the hull. My frame will be of either 1/8th or 3/16th 360 brass cut and filed to shape.

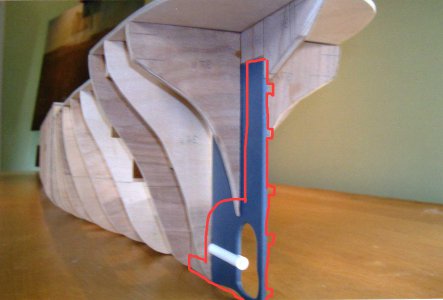

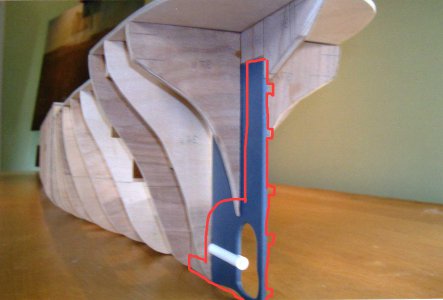

Here's an example of someone else's model with the stern frame made from blue plastic much like my brass frame will be constructed. My propeller shaft tube will be brass and soldered to the frame inside a slot.

I'm learning about various ways to solder and the solder wire involved and don't know what I should be looking for. Because this brass frame is so thick and the hull plates so thin, can I get away with standard 60/40 and a big iron as long as I pre-tin both surfaces? Should a micro torch be used instead? Will I experience previous joints coming undone as I try to solder successive layers of plates as I move upwards on the frame towards the top?

Various solder melting temperatures have me perplexed! I want to buy perhaps three temps of solder. I'll use the highest temp solder on maybe the stern frame-to-hull plating joints (or should I use the lowest temp for that?), then use the middle temp solder for the majority of the rest of the hull plate-to-plate joints, and then the lowest temp for whatever detail will be added on top of the other mid-temp joined parts. My question is what would you experienced solderers recommend be my three temps of solder? "Tix" brand at 275F, 60/40 at 370F, and some other silver solder at 400F+?

I know a lot of this will come with practice but right now I need to know what I should order. I've read that acid flux should be used on brass, but what about it corroding the steel plates? I'd really appreciate any direction from more knowledgeable builders. This ship will be built in phases. First phase is the hull just up to the superstructure. I'm sure I'll have to adjust my plan once I start building boxes with corners and windows/doors, etc. but for now my goal is the hull plating.

Thanks for your consideration.

-Tyler

I am in the beginning of a new project: a 1/144th scale RC model of the Titanic. The catch is that I've built a wooden former over which I'll solder 1/2"x 2-1/2" 0.010" tinplated steel pieces to recreate the look of the riveted 1" thick steel plates on the original. Once, completed, I'll remove the wooden former leaving an empty shell.

I have soldered a test sample of brass pieces to see if it was possible and was happy with the results. I think the tinplate will also be fairly straight forward as far as soldering but I'm having a little trouble planning some aspects.

The stern section will have a frame constructed of brass that the aftmost hull plates will terminate at and anchor to. Here's a picture of what I will be attempting. The red outline is what the frame will look like underneath the hull plates, inside the hull. My frame will be of either 1/8th or 3/16th 360 brass cut and filed to shape.

Here's an example of someone else's model with the stern frame made from blue plastic much like my brass frame will be constructed. My propeller shaft tube will be brass and soldered to the frame inside a slot.

I'm learning about various ways to solder and the solder wire involved and don't know what I should be looking for. Because this brass frame is so thick and the hull plates so thin, can I get away with standard 60/40 and a big iron as long as I pre-tin both surfaces? Should a micro torch be used instead? Will I experience previous joints coming undone as I try to solder successive layers of plates as I move upwards on the frame towards the top?

Various solder melting temperatures have me perplexed! I want to buy perhaps three temps of solder. I'll use the highest temp solder on maybe the stern frame-to-hull plating joints (or should I use the lowest temp for that?), then use the middle temp solder for the majority of the rest of the hull plate-to-plate joints, and then the lowest temp for whatever detail will be added on top of the other mid-temp joined parts. My question is what would you experienced solderers recommend be my three temps of solder? "Tix" brand at 275F, 60/40 at 370F, and some other silver solder at 400F+?

I know a lot of this will come with practice but right now I need to know what I should order. I've read that acid flux should be used on brass, but what about it corroding the steel plates? I'd really appreciate any direction from more knowledgeable builders. This ship will be built in phases. First phase is the hull just up to the superstructure. I'm sure I'll have to adjust my plan once I start building boxes with corners and windows/doors, etc. but for now my goal is the hull plating.

Thanks for your consideration.

-Tyler